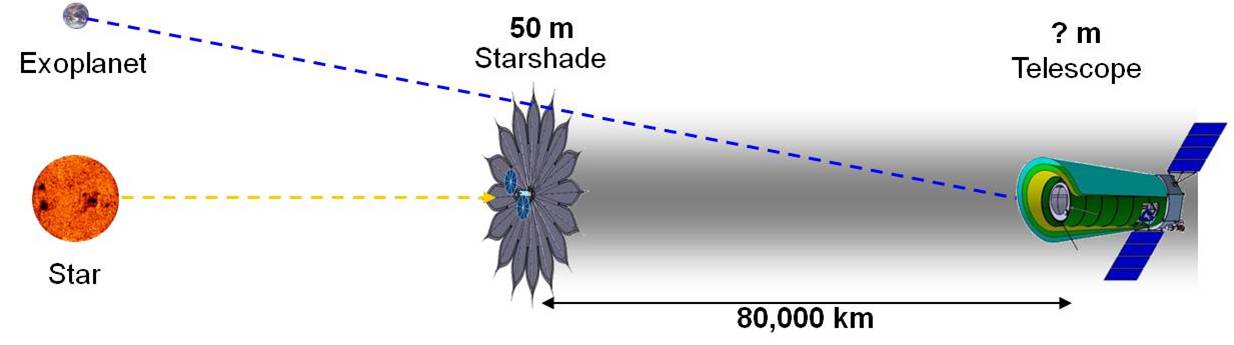

How ‘Starshades’ Could Aid Search for Alien Life – The next step in the exoplanet revolution may be an in-space “starshade” that lets alien worlds step out of a blinding glare. Researchers are testing designs for a starshade, which would fly in formation with a future space-based telescope. The starshade, also known as an “external occulter,” would block the light from a star while allowing the scope to spot emissions from much dimmer orbiting planets.

Scientists are conducting desert tests of the technology on Earth. They’re using the McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona to model a starshade’s ability to help future instruments find and characterize rocky, Earth-like alien worlds.

A starshade may be used on NASA’s potential Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), a space-based instrument that would feature a primary mirror 8 feet (2.4 meters) wide, the same size as that of the agency’s iconic Hubble Space Telescope.

Several years ago, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) donated two space telescopes to NASA. In 2013, the space agency announced it hoped to use one of these scopes for WFIRST. That move spurred anticipation in the U.S. astronomical community for Hubble-quality imaging over an area of sky 100 times larger than that viewed by Hubble. This version of the mission is called WFIRST-AFTA (for “Astrophysics-Focused Telescope Assets”).

The WFIRST-AFTA mission would carry out exoplanet exploration, dark energy research, and galactic and extragalactic surveys.

Desert and mountaintop testing

Small-scale versions of starshades have undergone nighttime desert testing in Nevada and California and, more recently, at the McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope site.

Credit: Northrop Grumman

The sites selected for evaluating starshade designs each have pros and cons, but collectively the evaluations are complementary and help to validate optical modeling of the idea, said Steve Warwick, Starshade program manager at Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems.

“We can’t do everything we can do in space on the ground in terms of optics, but the tests add a lot of confidence to how the starshade will work on orbit,” Warwick told Space.com.

McMath operators said testing sharshades with the telescope, which was dedicated in 1962, was the craziest way that anyone had used the facility to date, Warwick said.

“They were extremely helpful and excited to see what we could do with their facility,” Warwick said of the McMath team. Starshade testing at the Arizona site has been done twice so far, in late March and then in June.

The hope is to return to that location in the November-December time period; the exact timing will depend partly on other McMath users’ schedules, Warwick said.

A mix of NASA funding and Northrop Grumman funding has enabled the starshade test program to move forward.

Planet light

So what’s the big deal about starshades?

The technology — a flower-shaped screen that flies at a considerable distance from a space telescope —blocks starlight to create a high-contrast shadow. This shadow is so dark that only planet light enters a space telescope for examination by onboard instruments.

You can think of it as your big thumb blocking out blazing beams of light from the sun.

Tackling technology gaps

But a starshade in space has never seen the light of day, so to speak. While starshade engineers are drawing upon a successful track record of fielding large, deployable antennas in space, they must also beat back what are called “key technology gaps,” Warwick said.

Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

“For there to be a starshade launch with any telescope,” Warwick said, “we obviously need a lot of confidence that we’re going to get the science that we want to get.”

Both the desert trials and McMath mountaintop testing address a key technology gap — “that the optical models are trustworthy … that the models agree with what we measure,” said Warwick. He added that he thinks these gaps can be filled relatively soon.

“For me, where I sit, what excites me is the idea of being able to fly along with WFIRST,” he added.

Given the potential 2024-2025 launch of that instrument, a decision about whether to include a starshade on the mission could come in the next two to three years, Warwick said.

There are other possibilities beyond WFIRST as well. For example, the proposed 33-foot (10 m) Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared (LUVOIR) telescope and the projected Habitable Planet Explorer, or HabEx for short, could also incorporate starshades, Warwick said.

Snagging spectra

There is growing general support for WFIRST to include technology demonstrations of both a coronagraph (a light-blocking instrument that’s built into the space telescope) and a starshade (which flies separately), Warwick said.

“From our point of view, that’s a very exciting opportunity,” Warwick said. Such technology may enable spectra to be examined of some planets located in the “habitable zone” around their stars, where liquid water could exist on a world’s surface.

“A starshade with WFIRST could give us indications about habitable planets … but there’s a huge difference between ‘habitable’ and ‘inhabited,'” Warwick cautioned.

A larger telescope with a larger starshade could inform scientists about biosignatures from exoplanets, Warwick said, “and that would give us an indication of inhabited planets.”

But again, Warwick said, any biosignatures detected would not necessarily identify intelligent alien life. Rather, such signs would indicate some type of biological activity that has changed the planet’s atmosphere.

In pondering the larger cosmic picture, Warwick said he sees a starshade or something similar revealing that Earth life is not alone in the universe.

“I’ll take a bet that we will find signs of life outside of our solar system before we find it inside our solar system,” Warwick concluded.

Source: space